We took a closer look at Canada’s modern slavery reporting law, the Forced and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act, that came into effect in January. What does it mean for global workers’ rights, and can it achieve what lawmakers say it does – more transparency and an end to forced and child labour in supply chains? Let’s find out.

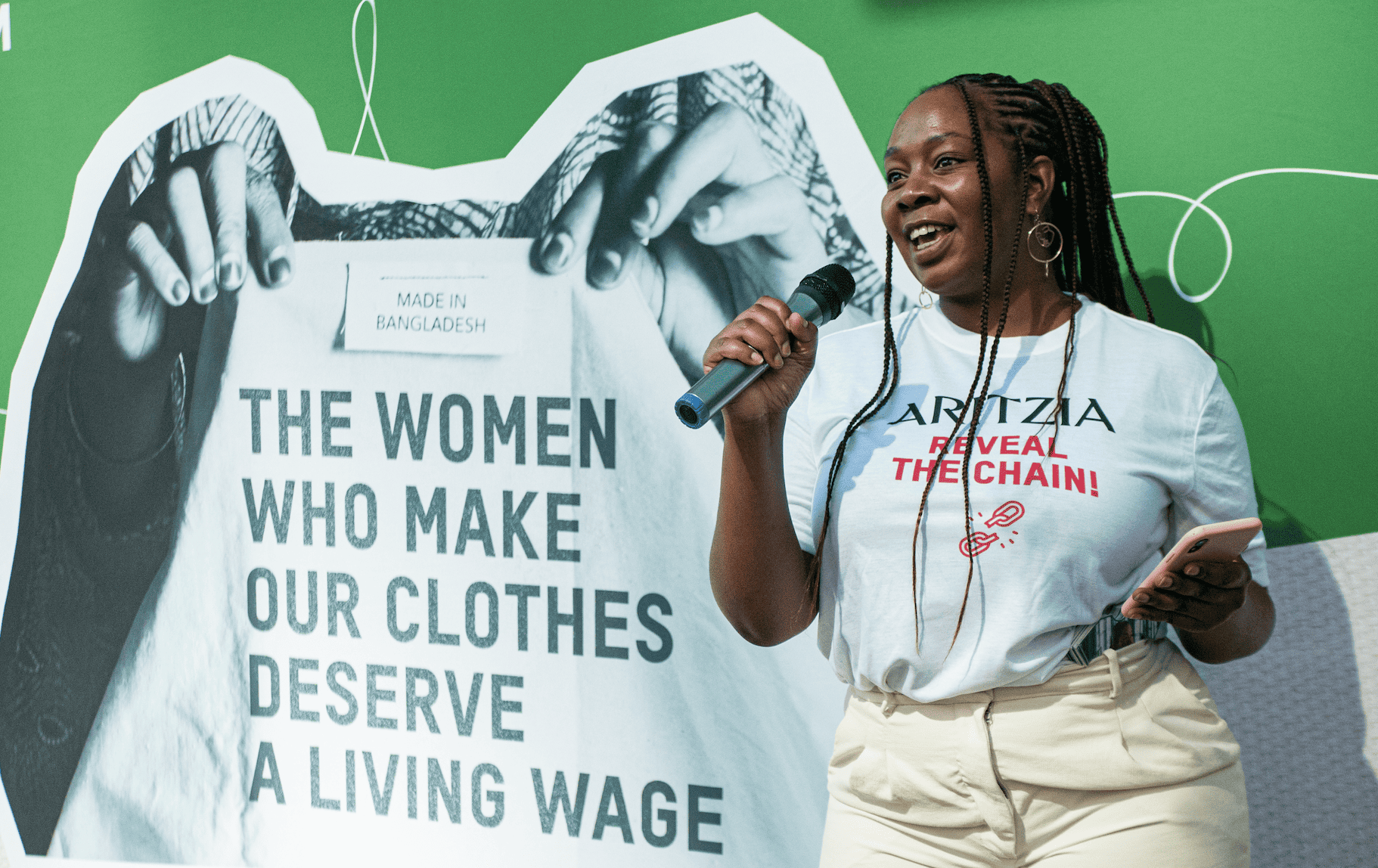

Aritzia

Disclosure of Policies and Due Diligence Processes: Reported having comprehensive policies and due diligence processes. Aritzia’s Supplier Code of Conduct remains publicly available, however, their Migrant Worker Policy, Child Labour & Young Worker Policy and Homeworker Policy are not publicly available.

Transparency: Reports sourcing countries but does not disclose specific factory names, locations, or addresses.

Supplier Monitoring: Conducts regular audits, assessments, and training programs. However, the effectiveness of social audits often falls short industry-wide due to poor-quality worker interviews and lack of genuine worker engagement.

Risk Assessment and Remediation Strategies: Acknowledges the risks of modern slavery and outlines steps for identification, prevention, and mitigation. There is no mandatory requirement for concrete remediation actions under Canada’s new law.

Prevalence of Forced Labour and Remediation Actions: Reported not being aware of or identifying any instances of forced labour or child labour during the reporting period.

Herschel

Disclosure of Policies and Due Diligence Processes: Reported having supplier code of conduct and due diligence processes but did not make these policies publicly available.

Transparency: Reports sourcing countries but does not disclose specific factory names, locations, or addresses.

Supplier Monitoring: Conducts regular audits, assessments, and training programs. However, the effectiveness of social audits often falls short industry-wide due to poor-quality worker interviews and lack of genuine worker engagement.

Risk Assessment and Remediation Strategies: Acknowledges the risks of modern slavery and outlines steps taken to prevent and reduce the risk of child and forced labour in its supply chains. There is no mandatory requirement for concrete remediation actions under Canada’s new law.

Prevalence of Forced Labour and Remediation Actions: Reported not being aware of or identifying any instances of forced labour or child labour during the reporting period.

Joe Fresh (Loblaw)

Disclosure of Policies and Due Diligence Processes: They reported having comprehensive policies and due diligence processes to address forced and child labour. Loblaw’s approach to human rights addresses the risk of modern slavery and is supported by its Colleague Code of Conduct, Supplier Code of Conduct and Loblaw’s Position on Human Rights. All of these policies are publicly available.

Transparency: Discloses information about their Tier 1 suppliers, including factory names, locations, and addresses on their website.

Supplier Monitoring: Conducts regular audits, assessments, and training programs. However, social audits are widely acknowledged to fall short industry-wide due to poor-quality worker interviews and a lack of genuine worker engagement.

Risk Assessment and Remediation Strategies: Acknowledges the risks of forced labour and child labour. Loblaw identified five inherent Salient Risks – forced labour, child labour, discrimination, harassment and abuse, livelihoods and occupational health and safety through their Human Rights Due Diligence (HRDD). Loblaw expanded their commitment to not knowingly source cotton or textile products using cotton produced in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Xinjian Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) of China due to widespread evidence of forced and child labour in their cotton harvests. There is no mandatory requirement for concrete remediation actions under Canada’s new law.

Prevalence of Forced Labour and Remediation Actions: Stated they “may receive reports of forced or child labour through our supply chain compliance and factory audits program” but did not disclose specific instances.

lululemon

Disclosure of Policies and Due Diligence Processes: Reported having comprehensive policies and due diligence processes. Lululemon’s policies and commitments include Global Code of Business Conduct and Ethics, Vendor Code of Ethics, Vendor Code of Ethics Compliance Benchmarks,

Foreign Migrant Workers Standard. All of these policies are publicly available.

Transparency: Discloses information about their suppliers, including factory names, locations, and addresses on their website.

Supplier Monitoring: Conducts regular audits, assessments, and training programs. However, the effectiveness of social audits often falls short industry-wide due to poor-quality worker interviews and lack of genuine worker engagement.

Risk Assessment and Remediation Strategies: Acknowledges the risks of modern slavery, including forced and child labour and outlines steps for identification, prevention, and mitigation. There is no mandatory requirement for concrete remediation actions under Canada’s new law.

Prevalence of Forced Labour and Remediation Actions: Acknowledged finding two instances of forced labour in its supply chain and reported subsequent remediation actions.

Roots

Disclosure of Policies and Due Diligence Processes: Reported having comprehensive policies and due diligence processes. Roots only publicly disclose their Vendor Workplace Code of Conduct, Supplemental Expectations, Employee Code of Conduct while other policies such as the Responsible Purchasing Practices, Critical Issues Policy are not publicly available.

Transparency: Discloses only the continents of their suppliers/third-party vendors.

Supplier Monitoring: Conducts regular audits, assessments, and training programs. However, the effectiveness of social audits often falls short industry-wide due to poor-quality worker interviews and lack of genuine worker engagement.

Risk Assessment and Remediation Strategies: Acknowledges the risks of modern slavery and outlines steps for identification, prevention, and mitigation. There is no mandatory requirement for concrete remediation actions under Canada’s new law.

Prevalence of Forced Labour and Remediation Actions: Reported not being aware of or identifying any instances of forced labour or child labour during the reporting period.

Our analysis reveals that while all five brands reported having policies and due diligence processes in place, the lack of public availability of many of these documents hinders external verification. Transparency varied, with Joe Fresh (Loblaw) and lululemon being more open about who their suppliers are. All brands reported regular supplier monitoring, but social audits are widely criticized for their limitations. Only lululemon acknowledged finding and remediating instances of forced labour. Overall, the findings highlight significant shortcomings in the legislation and the need for more robust, transparent, and enforceable measures to protect global workers’ rights.

Why Canada needs stronger legislation

While going through the legislative process, the Forced and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act was widely criticized for failing to address the deep-rooted human rights abuses and environmental impacts of Canadian companies operating abroad. Critics—including industry experts, civil society, and human rights activists—have condemned it as completely inadequate. We agree with them, and here’s why:

Weak reporting requirements without mandated action: The Act merely requires companies to report on measures to identify forced and child labour in their supply chains. There is no mandate for concrete action or verification, allowing companies to obscure the true extent of their complicity.

Lack of accountability: Companies are not obligated to confirm or deny the presence of forced labour and child labour within their supply chains. They retain the liberty to determine how much detail to disclose, rendering the reports potentially superficial and uninformative.

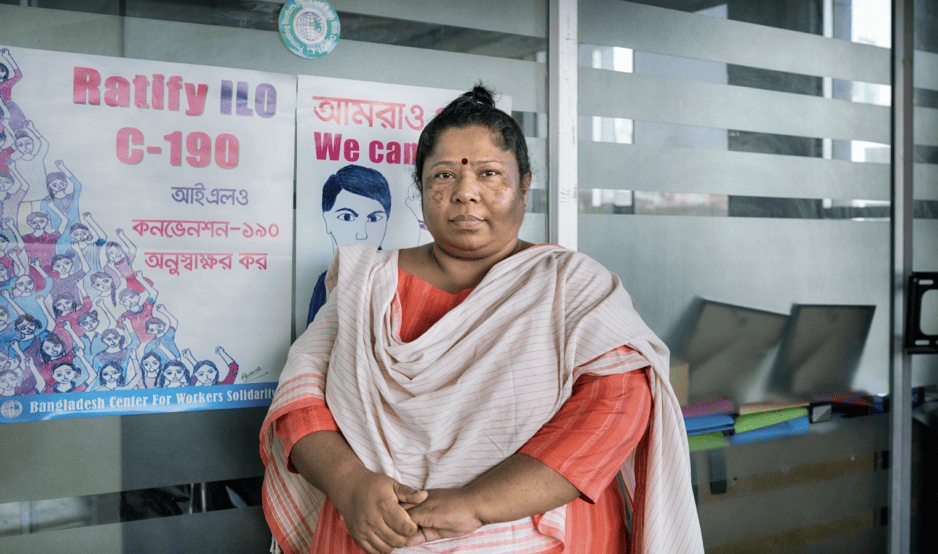

Ignores comprehensive human rights: The legislation fails to include comprehensive human rights, including women’s rights and the right to a living wage. Human rights are recognized as indivisible and interdependent, without hierarchy, and cannot be upheld in isolation. A law addressing only forced labour and child labour will fail unless it addresses human rights violations comprehensively.

Opaque Supply Chain: There is no mandatory reporting requirement to disclose detailed supply chain information, such as supplier names and addresses, product types, and the gender composition of the workforce. Opaque supply chains limit the ability of governments, civil society, workers, and rights holders to verify company claims and hold companies accountable.

Inadequate Remediation Mechanisms: The legislation lacks robust remediation mechanisms, protections against re-victimization, and guarantees of non-recurrence. Victims of forced labour are left without effective means to seek justice and redress.

Gender Blindness: The legislation lacks a gender lens and feminist approach. Women, particularly in the fashion industry, where they constitute the majority of the workforce, are disproportionately vulnerable to forced labour conditions. The Act’s failure to address this reality perpetuates gender inequality and exploitation. Canada should include gender-related protections and fulfill its commitment to upholding women’s human rights through laws, regulations, policies, and plans that address the unique challenges faced by women as rights holders. Legislation should require all Canadian companies to undertake gender-sensitive human rights due diligence. Additionally, legislation should require companies to adopt a proactive gender and non-discrimination policy, which is crucial to ensure that the companies’ policies and practices consider overlapping forms of structural discrimination through an intersectional lens.

Economic Injustice: The Act does not address the right to a fair wage, perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality. Workers remain trapped in exploitative working conditions and forced to work excessive overtime to cover their basic needs with no hope for economic improvement.

Fails to meet minimum UN standards: The legislation does not meet the basic standards set by the United Nations (UN), such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Governments should have stringent laws to protect people from human rights abuses by companies. However, Canada’s modern slavery reporting law falls short and lacks the necessary enforcement mechanisms and regulatory measures to hold businesses accountable.

Canada’s modern slavery reporting law, in its current form, is a superficial measure that offers no protection to the vulnerable workers in the supply chain. Recent revelations of Canada falling short on promises to block imports produced by forced labour further underscores the urgent need for stronger legislative measures.

To truly combat human rights abuses, Canada must introduce a robust corporate accountability law, such as the model law proposed by the Canadian Network on Corporate Accountability, The Corporate Respect for Human Rights and the Environment Abroad Act. Such legislation would require Canadian companies and companies importing goods into Canada to respect all human rights throughout their global supply chains, prioritize transparency and accountability with adequate enforcement mechanisms to hold corporations accountable, and provide access to remedies for those affected by human rights and environmental abuses.