By Lauren Ravon and Marty Warren

Adopting human rights and environmental due diligence legislation would help to advance Canada’s feminist foreign policy goals and gender equality measures in aid, trade, diplomacy, and defence.

Canada is facing a major test of its human rights and feminist credentials. Will the government put effective safeguards in place to ensure Canadian companies proactively respect human rights and the environment abroad?

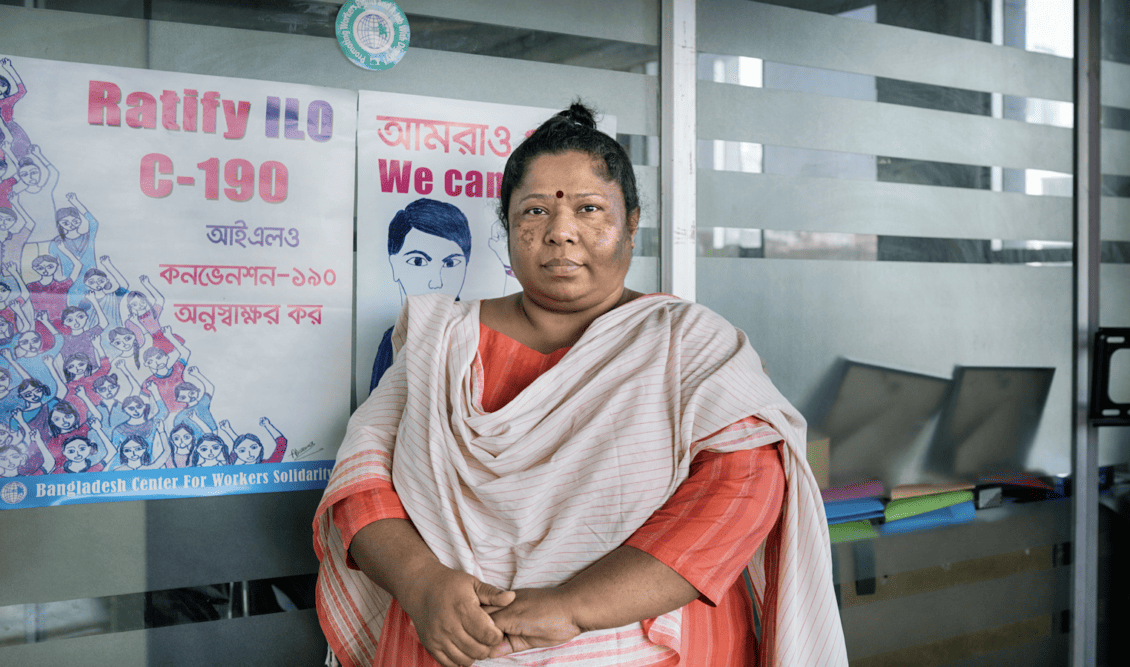

Our friend and colleague Kalpona Akter, a lifelong labour activist in the Bangladesh garment sector, has told us, “If my mum had received a wage we could live on, I wouldn’t have had to toil in a factory from the age of 12.”

Akter’s story is not unique, and living-wage violations are not the only human rights violations to occur in the fashion world. When the women who make our clothes try to form a union or ask for a raise, their jobs are at risk. Nine out of 10 workers in Bangladesh don’t make enough money to live on or afford food for their families. The women who make our clothes make poverty wages while the profits of Canadian fashion brands soar.

It’s promising that Labour Minister Seamus O’Regan’s mandate letter commits to “introduce legislation to eradicate forced labour from Canadian supply chains and ensure that Canadian businesses operating abroad do not contribute to human rights abuses.” The minister has made supply chain legislation his priority and is currently studying existing private members’ bills tabled in Parliament.

The question is: what kind of legislation will stop the abuse? Learning from other jurisdictions provides some insights.

Robust and comprehensive legislation must include the full range of human rights and have clear consequences for bad behaviour. Effective due diligence is not achieved through voluntary measures, reporting-only laws, or box-ticking compliance exercises. Canadian companies operating or sourcing abroad must be legally obligated to identify, prevent, mitigate, and provide remedies for all human rights violations and environmental damage caused by their operations.

Bill C-262, the Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights Act, currently before Parliament, meets global standards on mandatory human rights due diligence. It would ensure that Canadian companies across economic sectors proactively respect human rights and would help create a level playing field for business.

Another bill is Senate public bill S-211 on modern slavery reporting, which just passed second reading in the House with government support. Forced and child labour are deplorable and evidence has shown that progress on their elimination has stalled. This modern slavery reporting bill taps into the abhorrence Canadians have for such exploitation, but unfortunately does not create the legislative framework or tools to combat it.

Incredulously, S-211 requires companies to report on whether forced or child labour exist in their supply chains, but does not actually create a legal obligation on companies to stop the practice or to remedy the situation if found. S-211 is modelled on a similar law in the U.K. The experience of other jurisdictions shows that legislation centred on reporting has proven ineffective in addressing egregious labour abuses in global supply chains.

Some might suggest to “not let perfect be the enemy of good.” But is S-211 good? Modern slavery acts and their reporting-only requirements have not brought the change they promised to bring. Adopting S-211 would be like buying a train ticket to nowhere and expecting to arrive at your destination.

If the government is serious on stopping human rights abuses, a bill must include all human rights, robust accountability, and pathways to remedy. As Akter demonstrated in the introduction, her rights as a child were intimately connected to the labour rights of her mother. We will not protect children and eliminate forced labour by ignoring the indivisibility of human rights or adopting measures that do not enforce accountability.

A country’s foreign policy is not limited to the actions of state institutions, such as its embassies and armed forces, but also includes the international operations and business dealings of the private sector. Adopting human rights and environmental due diligence legislation would help to advance Canada’s feminist foreign policy goals and gender equality measures in aid, trade, diplomacy, and defence.

Canada’s mining sector is active in at least 100 countries and Canadian retailers import apparel from every continent, depending on a workforce largely dominated by women. Without oversight of the private sector, the Canadian government risks harming some of its bilateral relationships and setting back its feminist foreign policy objectives.

We are entering a critical moment for corporate accountability in Canada. After years of failed half measures, it is high time we deal meaningfully with the conduct of Canadian business abroad. Let this be Canada’s coming of age and let us learn from the European Union, France, Germany, and Norway with ambition, urgency, and pride.

Our organizations and global partners, representing millions of workers and feminists, believe Canada can and must do the right thing. We need mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence legislation in Canada. The time is now.

Human rights and accountability are non-negotiable.

This op-ed was originally published in The Hill Times on June 15, 2022.

Lauren Ravon is the executive director of Oxfam Canada. Marty Warren is the Canadian national director of the United Steelworkers.